On Whom We Cannot Instruct: Our Duty to Use Rhetoric

- Aristotle, Rhetoric, Book I Part I [*1]Before some audiences not even the possession of the exactest knowledge will make it easy for what we say to produce conviction. For argument based on knowledge implies instruction, and there are people whom one cannot instruct.

Much of human experience is unfurled by those two sentences of Aristotle. Some choose what to believe and/or how to act based on information, but a surprising number are incapable. And how we communicate with those incapable matters acutely to the health of civilizations.

Beliefs of children derive from social consensus of family and other authorities. Going against consensus often cuts children off from resources only their authorities can provide. Access to resources socializes children to deference to their authorities, as values and orders are instilled. The job of children is not so much to think, but to comply with orders and memorize answers, face punishment for non-compliance and unapproved answers, and receive rewards for compliance and approved answers.

Of course, much of the time, these answers are correct, and to instruct on how and why wastes time on children who've yet to develop the ability to think critically. Too many behaviors and beliefs need to be instilled in a short period of time for a child's knowledge to be foundational. So, instead, children's knowledge flows from their superiors' decree.

By the time we're adults, hopefully we've developed critical-thinking skills, which we use to form our own conclusions about the world and how to live our lives. How do we know when we and those we are communicating with are exercising such skills? How do we discern who is capable and, more importantly, incapable of such skills? How do we manage people who are incapable?

Aristotelean Dialectic and Rhetoric

We can't foundationally know the exact nature of other people's thoughts. But, since they communicate to discover and/or change what others are thinking, we in turn can approximate their thoughts by interpreting what they communicate. We observe thoughts through actions, like discerning an invisible object by detecting the movements of its shadow and sounds it makes. The shadows and sound give incomplete information on the shape of the object, but enough for you to move out of the way if you hear it moving toward you. By analyzing the logic we see communicated and approximating the emotions involved in the responses, we interpret the thoughts of others. And by interpreting the responses to our communication, we learn how to communicate, and more importantly, on whom different forms of communication should be used.

As Aristotle suggests, there are two fundamental forms of human communication: dialectic and rhetoric. Dialectic involves the use of logic. Rhetoric involves the use of emotion.

For a simple example of dialectic: if everyone around you claims jumping off a bridge is fun, you could conclude that, because your past experience of falling down while running caused pain and/or injury, a fall from a bridge, being a much greater height than your past falls, would likely result in proportionally more pain and/or injury. Thus, the claim our peers and authorities make is determined invalid, and you opt not to jump off the bridge. Your articulation of these thoughts is dialectic. That raw logic is all one needs to know not to jump off the bridge. A response like "don't be a coward," is rhetoric. It's also valuable information; it tells you the person is incapable of reason, at least in this particular instance.

For a simple example of rhetoric: in deciding whether to jump off a bridge, you note that, while the majority are claiming it is fun, an attractive woman you hold in high regard tells you only idiots jump off bridges. Because you wish to win her favor, you believe she is likely correct, and, thus, choose not to jump off the bridge. Here, the word part of the rhetoric is "only idiots jump off bridges." But the words alone don't make the rhetoric effective; it's the beauty and status of the woman, here, that empowers her words. Rhetoric communicates through emotion; and status, beauty, vocal inflection, font, and countless other factors are part of that communication.

In both methods of understanding, you have reached the correct conclusion: to refrain from jumping off the bridge. In the former, you are using information, inductive reasoning to make your decision. In the latter, you are responding to emotion, the need to feel esteemed by those you hold in high regard, to make your decision.

Most of us respond to both dialectic and rhetoric on a daily basis. Almost all advertising is rhetoric, as it tries to persuade by appealing to the audience's emotions. Almost all legal battles before a judge (read: not a jury) are dialectic, as the lawyer uses reason to persuade the judge.

In a sense, dialectic and rhetoric are like different languages. All humans understand rhetoric by instinct, since we are born with emotions. But reason takes some training to develop, and, perhaps, as Aristotle suggests, is a language some are incapable of learning.

"They Will Forget What You Said and Did But Never Forget How You Made Them Feel"*

Just as a multilingual person shouldn't speak English to Spanish-only speakers, dialectic speakers shouldn't attempt reason with those incapable of logic. Just as the Spanish-only speaker will hear English words and relate them, where possible, to Spanish in an effort to understand, the rhetoric-only speaker will look to the emotion the dialectic-speaker's words instill to understand.

In the modern world of mass communication, our audiences are often too large to anticipate the consequences of our words only in reason. A dialectic speaker must consider the possible range of emotions his words could stir, proportionally with the size of his audience, since those limited to rhetoric increase in number with the size of the audience, and, in some audiences, may be the vast majority.

Almost all speeches necessarily rely on rhetoric, because, eventually, the information in the speech is forgotten, and only one-liners are remembered like "We choose to go to the Moon" or "Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall." The how and why to get to the Moon aren't remembered in a dialectic fashion but in a rhetorical sense: "because it is hard," as the audience swells in ego, since "we" means them and people like to be seen as capable of doing "hard" tasks that their peers around the world will admire. The how and why the Soviet Union should destroy the Berlin Wall aren't remembered, just the emotional resonance of imagining families united.

The Limitations of Dialectic

It is difficult to convince someone to go along with an incorrect instruction using dialectic, as reason naturally leads to either correct conclusions or, if we are honest, an admission that more information is needed to make the correct conclusion. Those who can understand dialectic examine the informational basis behind others' opinions to determine how likely the opinion is to be true. Dialectic thinkers wonder what information is needed to make an opinion more or less valid. They discern the best probable course of action or probable truth with the information that is known, but rarely do they know with absolute certainty, because new information can always change their views.

For example, at a gym I saw a shower with the red and blue color markers for hot and cold on the handle and assumed turning the handle to red would cause hot water. Cold water continued to come out, and the water wasn't getting hotter. I could have concluded the shower was broken, but the cold water informed me that the information I had was wrong. The red and blue markers were reversed. Thus, I turned the handle in the other direction and got hot water.

Opinions are only as good as the available information. And, since human experience allows for only limited ability to receive information, most of our convictions must be probabilistic instead of absolute. You know it is raining outside if you feel the rain drops pour from the observable sky upon you. You know it is probably raining outside if someone walks into your windowless room with a wet umbrella. What information would change your knowledge? Perhaps you discover he dipped his umbrella in a bucket of water before entering.

Only God can know the true nature of the universe (or nobody, atheists suppose). The dialectic thinker accepts this and makes most of his decisions in life with confidence instead of certainty.

The Boundless Confidence of Rhetoric

Rhetoric is a more-powerful communication tool than dialectic when it comes to material change. The persuader looking to organize people to accomplish a goal can convince his audience to do what is asked with reason alone. But, to convince with conviction requires emotion, and rhetoric stirs the emotions to make people work toward the goal with enthusiasm.

While a dialectic thinker understands in probabilistic terms, the rhetorical thinker is prone to absolutes. Recall the jumping-off-a-bridge example of earlier. What new information could change the hesitant jumper's mind? Perhaps there is a giant cushion underneath to break the fall from the bridge. This information is unlikely to change a rhetoric-thinking jumper's mind, because the woman he wishes to earn favor from believes anyone who jumps off a bridge is an idiot, and the thought of earning her favor guides his decision.

Most of our daily decisions are guided by rhetoric, because dialectic takes too much time. Without emotion, how would you decide what to prepare for dinner, where to go for vacation, or when to marry and have children? Logic brings surprisingly little direction to many of our life-changing decisions. As emotions are intrinsic to the human condition, rhetoric is intrinsic to human communication. Dialectic is merely an art used in limited circumstances to improve our lives.

You might be inclined to communicate with dialectic instead of rhetoric wherever possible, but Aristotle reminds us that we have a duty to use whatever communication style is effective in doing good. Persuasive communication is unique to humans, and failure to persuade is the fault of the persuader.

Imagine choosing between a giant hammer or a spear for combat. Normally, we'd be inclined to use the spear, as it has long reach and sharpness to penetrate our foes. If the foe is wearing plated armor, however, suddenly the hammer seems the wiser choice.

The dialectic speaker trying to do good before an audience incapable of understanding is like the spear-wielding warrior trying to attack the armored foe. What would normally be the superior weapon becomes the inferior one. Thus, both dialectic and rhetoric must both be part of the arsenal of the man hoping to maximize good, and the tools' deployments will be conditional on the types of audiences presented.

The Conflation of Rhetoric with Dialectic

What's the easiest way to know if we are truly communicating in dialectic instead of rhetoric?

Dialectic is a conversation to discover truth, regardless of what that truth might be. Rhetoric-based persuasion is used when we seek solely to persuade others, regardless of what the truth might be. Dialectic persuasion involves being open to the possibility of different answers, and the persuasion is simply a means to test the perceived best arguments against any possible better ones.

Recall I stated earlier that a lawyer uses dialectic to persuade a judge on a legal question. The judge's job is to consider all the different possible answers to a legal question and use the arguments by the opposing lawyers against each other to test for the best answer. In a healthy judiciary, rhetoric will never persuade a judge on a legal question. Ideally, the lawyer skilled in dialectic but with the weaker position will explain to his client why he is likely to lose before wasting his client's time and/or money on the argument. In a just society, a good lawyer's art is his ability to accurately predict the result for his client more than his ability to persuade the judge, because the judge should have the superior dialectic reasoning to come to the correct result regardless of the lawyer's skill in presenting an argument.

In an unjust society, the lawyers and political tacticians have the ability to achieve desired results over correct results. For a better chance at the desired outcome, the intelligent must be persuaded along with those limited to rhetoric. Since those deficient in understanding dialectic often find their opinions by looking to the beliefs of those they perceive as intelligent, winning the intelligent has a bonus effect. Further, since politics involves orders from multiple authorities with the power to compel people to do things they disagree with, and those in positions of authority are usually more intelligent, persuading the intelligent is necessary to achieve desired political results that are contrary to justice.

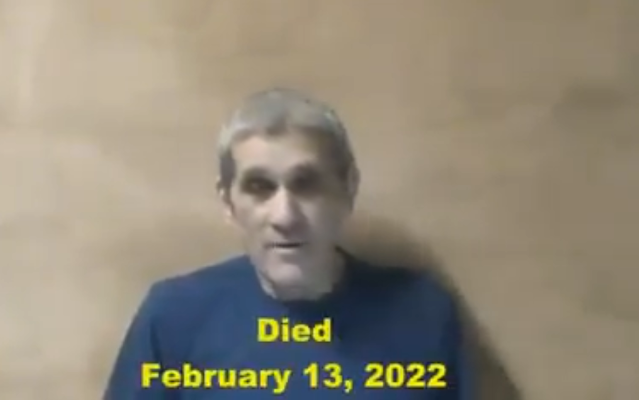

When intelligent people are among those needed for persuasion, the most effective communication involves cloaking rhetoric in the guise of dialectic. Since reason leads to the correct result more than a desired result, skilled rhetoricians cloak their arguments in seeming dialectic to get what they desire under the pretense of sophistication. In our 2020-? global "pandemic," Anthony Fauci has been a great example. As a bureaucrat for the National Institute of Health and not a practicing physician, why did he wear a white lab coat when speaking? When he was asking Americans to use masks, what evidentiary basis did he have for demanding it? Why did he switch from discouraging to encouraging masks in the course of a month? What was the so-called scientific evidence that changed his view?

In the debate of whether to jump off a bridge, if an attractive authority says she believes the bottom of the bridge has a sufficient cushion when she has no basis for her claim, she is wearing dialectic as a skinsuit for communication. False information is introduced in the hopes of getting the result she wants, in that case, your death or injury.

Our post-pandemic wicked world of politics twisting with "science" is rife with examples of fake dialectic. In January 2021, I put out a piece on the pandemic [*2] that mourned the harm of political solutions, like lockdowns, masking, and forced vaccinations, in the short-run but warned of the death of civilization in the long-run, since the constant changing narratives and confidently-stated recommendations turning out wrong or bringing about the opposite of the intended result meant the consensus of authorities projected to us by the media could not be trusted and, without that trust, civilization, at least in its more globalist-oriented form, could not properly function.

First, an argument was made that lockdowns were needed to "slow the spread" in order save hospital beds for the anticipated infected who would need them. Then, masks were argued to help reduce the spread. Then, the same was argued of vaccines. Of course, none of this was objectively true, and it's increasingly observable that the exact opposite is the case, but those snake-tounged in dialectic ask their audience to imagine how much worse it would have been but for their recommendations being followed.

One of the earliest lessons in spotting this fraudulent form of dialectic was given in a Sesame Street skit between Bert and Earnie [*3]. Bert observes Earnie with a banana in his ear and asks why. Earnie responds that he is doing so to keep the alligators away. Bert says there are no alligators on Sesame Street. Earnie responds: "Right. It's doing a good job, isn't it Bert?"

The Purity of Dialectic

While rhetoric can be disguised as dialectic, the reverse is not possible. We can add rhetoric to dialectic, but they remain two distinct communications.

If I say, "Only idiots jump off bridges" and then articulate my prior-stated reasoning as to why we shouldn't, I am speaking in two languages in the same manner public safety signs often warn in two languages. The two texts on the safety sign don't together form the warning; they exist to warn the ones who can't read the other language. Similarly, for my warning not to jump off the bridge, I am trying to do good by communicating in rhetoric and dialectic, in case the person I'm speaking to can't understand reason.

Rhetoric, however, can pretend to be dialectic, depending on how it's used, just like English pretends to be another language in Pig Latin, but is really still English. If I wear a white lab coat on cable television and claim "the currently-evolving research says jumping off a bridge might be good for your health," while the news anchors nod their heads in agreement and thank me for my time, I am disguising my rhetoric in the pretense of reasoning, because "evolving research" and "might" allows me to avoid a commitment to specific facts to back up my inference that we should jump off the bridge. If you foolishly listen to me, you're trusting in the white coat, my credentials, and the fact that the news anchors are nodding their heads to me. I'm really using rhetoric, no different than the pretty woman telling you that "only idiots jump off bridges."

The Art of Rhetoric

Understanding when and how to use rhetoric involves understanding how our communication impacts others. Recall I stated we can't know the exact nature of another's thoughts. We infer them by what they communicate in response. We don't see the thought; we see or hear the words articulating them. We don't see the emotion; we see the body language, eyes, and facial expressions and hear the vocal inflections, pitch, cadence and volume.

Why do lawyers often insist on meeting with their clients in person? The lawyer often asks complicated questions and gives complicated instructions. When I ask questions, I can often tell whether the answer is correct or not, through the clients' body language. By reading body language, I can tell when clients aren't understanding my question or are holding something back. I can also tell whether they truly understand my instructions or not. This gives the opportunity to ask my questions or give my instructions differently, to ensure I have their understanding.

In a just society, law leans heavily toward dialectic communication, since justice is about bringing a logical consequence to the truth, and courts are about discovering the truth and applying justice. Judges and juries (in a just society, after being given an IQ test before admission) read the emotions broadcast by witnesses to decide this.

In rhetoric, reading emotions is even more important, if not all that matters. Effective rhetoric is about influencing the emotions of others. The key word here is others. The speaker must not conflate his emotions with that of his target audience. When I hear the words of then-president John F. Kennedy, "We choose to go to the Moon. ... not because it is easy, but because it is hard," I cringe. Why should taxpayers commit an absurd amount of resources on a task, just because it is "hard?" Nonetheless, young boomers must have swelled in emotion after hearing it, because it is one of the few commitments the regular person in 2022 remembers Kennedy by, as the emotional resonance carried forward into the 21st century.

Author Vox Day often states that rhetoric has no information content. It's defined by its utility more than its form, just as a shovel that could be used as a weapon is defined by its effect of digging and not its utility in combat. Rhetoric's effect is its emotional influence, regardless of the exact words used in its communication. When the attractive woman says, "Only idiots jump off bridges," there is no information on why we should refrain from jumping off the bridge. The recipient of her words is reacting to the emotional pain behind rejection from an attractive woman.

Dialectic is a conversation to discover truth, regardless of what that truth might be. Rhetoric-based persuasion is used when we seek solely to persuade others, regardless of what the truth might be. Dialectic persuasion involves being open to the possibility of different answers, and the persuasion is simply a means to test the perceived best arguments against any possible better ones.

Recall I stated earlier that a lawyer uses dialectic to persuade a judge on a legal question. The judge's job is to consider all the different possible answers to a legal question and use the arguments by the opposing lawyers against each other to test for the best answer. In a healthy judiciary, rhetoric will never persuade a judge on a legal question. Ideally, the lawyer skilled in dialectic but with the weaker position will explain to his client why he is likely to lose before wasting his client's time and/or money on the argument. In a just society, a good lawyer's art is his ability to accurately predict the result for his client more than his ability to persuade the judge, because the judge should have the superior dialectic reasoning to come to the correct result regardless of the lawyer's skill in presenting an argument.

In an unjust society, the lawyers and political tacticians have the ability to achieve desired results over correct results. For a better chance at the desired outcome, the intelligent must be persuaded along with those limited to rhetoric. Since those deficient in understanding dialectic often find their opinions by looking to the beliefs of those they perceive as intelligent, winning the intelligent has a bonus effect. Further, since politics involves orders from multiple authorities with the power to compel people to do things they disagree with, and those in positions of authority are usually more intelligent, persuading the intelligent is necessary to achieve desired political results that are contrary to justice.

When intelligent people are among those needed for persuasion, the most effective communication involves cloaking rhetoric in the guise of dialectic. Since reason leads to the correct result more than a desired result, skilled rhetoricians cloak their arguments in seeming dialectic to get what they desire under the pretense of sophistication. In our 2020-? global "pandemic," Anthony Fauci has been a great example. As a bureaucrat for the National Institute of Health and not a practicing physician, why did he wear a white lab coat when speaking? When he was asking Americans to use masks, what evidentiary basis did he have for demanding it? Why did he switch from discouraging to encouraging masks in the course of a month? What was the so-called scientific evidence that changed his view?

In the debate of whether to jump off a bridge, if an attractive authority says she believes the bottom of the bridge has a sufficient cushion when she has no basis for her claim, she is wearing dialectic as a skinsuit for communication. False information is introduced in the hopes of getting the result she wants, in that case, your death or injury.

Our post-pandemic wicked world of politics twisting with "science" is rife with examples of fake dialectic. In January 2021, I put out a piece on the pandemic [*2] that mourned the harm of political solutions, like lockdowns, masking, and forced vaccinations, in the short-run but warned of the death of civilization in the long-run, since the constant changing narratives and confidently-stated recommendations turning out wrong or bringing about the opposite of the intended result meant the consensus of authorities projected to us by the media could not be trusted and, without that trust, civilization, at least in its more globalist-oriented form, could not properly function.

First, an argument was made that lockdowns were needed to "slow the spread" in order save hospital beds for the anticipated infected who would need them. Then, masks were argued to help reduce the spread. Then, the same was argued of vaccines. Of course, none of this was objectively true, and it's increasingly observable that the exact opposite is the case, but those snake-tounged in dialectic ask their audience to imagine how much worse it would have been but for their recommendations being followed.

One of the earliest lessons in spotting this fraudulent form of dialectic was given in a Sesame Street skit between Bert and Earnie [*3]. Bert observes Earnie with a banana in his ear and asks why. Earnie responds that he is doing so to keep the alligators away. Bert says there are no alligators on Sesame Street. Earnie responds: "Right. It's doing a good job, isn't it Bert?"

The Purity of Dialectic

While rhetoric can be disguised as dialectic, the reverse is not possible. We can add rhetoric to dialectic, but they remain two distinct communications.

If I say, "Only idiots jump off bridges" and then articulate my prior-stated reasoning as to why we shouldn't, I am speaking in two languages in the same manner public safety signs often warn in two languages. The two texts on the safety sign don't together form the warning; they exist to warn the ones who can't read the other language. Similarly, for my warning not to jump off the bridge, I am trying to do good by communicating in rhetoric and dialectic, in case the person I'm speaking to can't understand reason.

Rhetoric, however, can pretend to be dialectic, depending on how it's used, just like English pretends to be another language in Pig Latin, but is really still English. If I wear a white lab coat on cable television and claim "the currently-evolving research says jumping off a bridge might be good for your health," while the news anchors nod their heads in agreement and thank me for my time, I am disguising my rhetoric in the pretense of reasoning, because "evolving research" and "might" allows me to avoid a commitment to specific facts to back up my inference that we should jump off the bridge. If you foolishly listen to me, you're trusting in the white coat, my credentials, and the fact that the news anchors are nodding their heads to me. I'm really using rhetoric, no different than the pretty woman telling you that "only idiots jump off bridges."

The Art of Rhetoric

Understanding when and how to use rhetoric involves understanding how our communication impacts others. Recall I stated we can't know the exact nature of another's thoughts. We infer them by what they communicate in response. We don't see the thought; we see or hear the words articulating them. We don't see the emotion; we see the body language, eyes, and facial expressions and hear the vocal inflections, pitch, cadence and volume.

Why do lawyers often insist on meeting with their clients in person? The lawyer often asks complicated questions and gives complicated instructions. When I ask questions, I can often tell whether the answer is correct or not, through the clients' body language. By reading body language, I can tell when clients aren't understanding my question or are holding something back. I can also tell whether they truly understand my instructions or not. This gives the opportunity to ask my questions or give my instructions differently, to ensure I have their understanding.

In a just society, law leans heavily toward dialectic communication, since justice is about bringing a logical consequence to the truth, and courts are about discovering the truth and applying justice. Judges and juries (in a just society, after being given an IQ test before admission) read the emotions broadcast by witnesses to decide this.

In rhetoric, reading emotions is even more important, if not all that matters. Effective rhetoric is about influencing the emotions of others. The key word here is others. The speaker must not conflate his emotions with that of his target audience. When I hear the words of then-president John F. Kennedy, "We choose to go to the Moon. ... not because it is easy, but because it is hard," I cringe. Why should taxpayers commit an absurd amount of resources on a task, just because it is "hard?" Nonetheless, young boomers must have swelled in emotion after hearing it, because it is one of the few commitments the regular person in 2022 remembers Kennedy by, as the emotional resonance carried forward into the 21st century.

Author Vox Day often states that rhetoric has no information content. It's defined by its utility more than its form, just as a shovel that could be used as a weapon is defined by its effect of digging and not its utility in combat. Rhetoric's effect is its emotional influence, regardless of the exact words used in its communication. When the attractive woman says, "Only idiots jump off bridges," there is no information on why we should refrain from jumping off the bridge. The recipient of her words is reacting to the emotional pain behind rejection from an attractive woman.

An observer against jumping off the bridge who doesn't find the woman attractive and/or believes the woman herself is an idiot might not find this rhetoric effective. But that's not the point. Effective rhetoric is about the emotions of the target audience, in this case, those lacking the cognitive function to understand that jumping off a bridge will cause severe injury, pain, and/or death. Whether the rhetoric is effective on people who already know not to jump off the bridge is irrelevant.

Effective Rhetoric

Vox Day also observes that effective rhetoric points in the direction of truth. The effectiveness of calling those who jump off a bridge idiots is amplified by the fact that choosing not to jump off the bridge is the correct choice. Depending on how we define "idiot," the statement may be correct. And, in discussing whether those deciding to jump off a bridge are idiots or not, and backed up by sufficient reasoning, "Only idiots jump off bridges" can be a dialectic statement. But in influencing people not to jump, it is a rhetorical one.

This is why calling someone a landwhale when she is overweight is probably effective rhetoric to get her to adopt a certain diet, while calling a skinny person the same pejorative is probably ineffective or at least less likely to be effective. And it may explain why spouses can get into such heated arguments with each other, as their rhetoric involves exaggerating claims that, while not strictly correct, point in the direction of the truth about each other.

In politics, a historical example of effective rhetoric was calling a twentieth century, left-leaning American a "pinko." The color "pink" meant one was shading toward the color of communists, red, which was the color associated with the U.S. rival at the time, the Soviet Union, and conservatives of the era naturally had a broader definition of "communist" than liberals did. Regardless of any fair definition, to be associated with a U.S. enemy during the 1920s (e.g., Wall Street Bombing of 1920 [*4]) through the Cold War inferred the possibility of being prosecuted. The rhetoric "pinko" was used to get liberals not to discuss their political views as openly by playing to this fear. Even if a twentieth-century liberal didn't want to be associated with communism, then-liberal politics was about pushing policies shared with communist ideals, even if then-liberals didn't want their views to go exactly that far. "Pinko" pointed in the direction of the truth.

In modern politics, calling any right-leaning person a "racist" has similar rhetorical power. To be associated with racists means potential employers, career networks, family, and social groups could socialize ostracize you in the phenomenon we refer to as "cancel culture" [*5].

Just as "pinko" pointed in the direction of the truth regarding twentieth-century liberals' so-called "communist" beliefs, even if by stricter definitions liberals were not communists, "racist" points in the direction of truth regarding a 2020s right-leaning individual. That is, if 1950s liberal ideas truly had no relation at all to communism, then the rhetoric would have been shrugged off. Nobody would have used the word. If 2020s right-wing ideas truly have no relation at all to racism, the term racist would not be as widely circulated as it is.

Why does "racist" hit the mark so well? The left defines the term incredibly broadly. From Jim McWhorter at the Atlantic [*7]:

While right-leaning people can ridicule such a definition as absurd, they have to ask themselves: at which narrower definition of racist (and there are many) does the term start to apply to them?Today, racist means not only burning a cross on someone’s lawn or even telling someone to go home, but also what feels unpleasant to someone of a race—as in what I as a person of that race don’t like. It has gone from being mean to someone to, also, what feels mean to me.The two may seem the same, but it gets tricky. A white woman admires a black woman’s locks and asks her how she washes them; the black woman gets tired of answering such questions and feels they are intrusive, harmful. Many would instinctively extend the term racist to this interaction, despite the fact that the white woman sincerely admired the black woman’s hair and feels odd being called a racist.

Much of the right or conservative-leaning people identify with nationalism. A nation is a lineage of people living in a geographic area. Nation is a subset of race, as family is a subset of nation. Love of family is love of your living blood line. Why do we love our family over our friends [*6]? What role does race play in it?

Is a right-leaning person or conservative who doesn't prioritize love of family truly one of the right? While conservatives can argue how the love of family is different from love of nation or race, the term "racist" as applied to a lover of family still points in the direction of truth. One might love his brother more than his third cousin, but at what point does the blood thin enough where the love of family disappears? What separates love of family from love of friends? Does love of family mean one necessarily loves his race over others, even slightly?

For the early-to-mid twentieth century left-leaning person, the label "pinko" also pointed in the direction of truth in the context of intense social pressures against the Soviet Union and its communist satellites as U.S. rivals. But, in the twenty-first century, the reason "racist" is effective rhetoric and "pinko" is not has entirely to do with the popular culture and people's perception of negative emotional baggage tied to the word. One day, "racist" will lose its rhetorical steam, akin to how "pinko" did, and new terms will rise in rhetorical dominance.

Rhetoric in Our Age of Mass Communication

In our modern era, memes function as probably the most powerful rhetoric, especially as generations accustomed to mass-communication devices become old enough to commonly hold positions of power. A meme is visual rhetoric, pointing out an absurdity with usually short phrases and simple or crude pictures. The more a meme points to the truth, the more effective it can be.

Effective memes make certain ideas more or less socially acceptable to discuss. We measure a successful meme by how much support the meme gets among like-minded people, but also by how much the opponents attack it in a dialectic fashion. Memes often contain minor errors in spelling or grammar, and most people find it amusing when others complain about these errors. No meme is dialectically correct; otherwise, it wouldn't be a meme but an infographic. And there is something jarring about responding to rhetoric with dialectic. The person criticizing a meme is confessing that he feels the social ostracism suggested by the meme and is trying to stop its spread.

It is commonly said that people often form their opinions by feeling and then use reason to defend them. To the extent people use reason to justify opinions akin to comfortable emotional states, rhetoric is more effective than reason, because it can change the emotional state of the target.

Imagine one twenty pounds overweight responding to being called a landwhale by stating that whales are orders of magnitude heavier than him. He might even note that person X calling him a landwhale is taller with bigger muscles and thus weighs more, making person X the real landwhale. Observers note that the fact that one is even defending his alleged landwhale qualities is a confession that he is a socially unacceptable weight and, thus, subject to ridicule. The same is true of right-leaning people responding to the charge of racist with an explanation of why they are not racist. This is especially true for right-leaning people who say "you guys are the real racists."

How Can Rhetoric Guide Human Flourishing?

In a better world, all people could speak dialectic. We do not live in that world. None of us even live in that kind of nation. Few of us even live in such families. This may have to do with genetic intelligence and/or the way children are raised, but, regardless, we must deal with the reality that "there are people whom one cannot instruct." And, since modern society involves mass communication, we will naturally be dealing with many people whom we cannot instruct.

Rhetoric is an art that should be applied at the appropriate intensity for the appropriate audience at the appropriate time. Effective rhetoric in 2016 was not the same as effective rhetoric in 1960 and won't be the same in 2024. While the same kinds of emotions are at play, the levers to manipulate such emotions change over time. Today's "based" is tomorrow's "cringe." Rhetoric is about knowing what your audience cares about on a deeply personal level. It can be used to rally an audience toward a particular objective: "We choose to go to the Moon... not because it is easy, but because it is hard." It can be used to shut down opponents: "stop being such a racist."

Regardless of the rhetoric we use, we don't do so in a vacuum. From advertising to endless forms of other media to the whims of friends and family, countless factors in our lives function as rhetoric, as they tug our emotions toward favoring or disfavoring particular actions and ideas. Retoric is integral to the social experience. We cannot escape it. As such, our duty is to bend and apply it toward what we discover by reason and the values we've discovered by the same, to maximize goodness and flourishing.

--

FOOTNOTES

[*1] http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/rhetoric.1.i.html

My intitial introduction to Aristotle's Rhetoric came from Vox Day's book, SJWs Always Lie (2015) https://arkhavencomics.com/product/sjws-always-lie/

[*2] https://stratagemsoftheright.blogspot.com/2021/01/the-broken-thumb-heuristics-in-fall-of.html

[*3] I originally heard this reference from E. Michael Jones, whose video content, unfortunately, has been scrubbed from the internet. The Sesame Street clip he references can be watched here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zwsmqZLCKPE

[*4] https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/wall-street-bombing-1920

[*5] https://stratagemsoftheright.blogspot.com/2021/03/the-ontology-of-cancel-culture-racists.html

* This thought is commonly attributed to Maja Angelou.

[*6] Modern leftism and popular culture is about destroying the distinction of blood family by promoting the message that family can be friends as well as blood. There are countless examples of this in modern entertainment. As an egregious example, the modern Hollywood franchise "Fast and the Furious" went a little overboard with propaganda, with the skinnier of the two muscle-bound anti-heroes constantly talking about the strength of "family," referring to his non-blood, multi-racial cast of criminal accomplices. The popularity of the meme, ironically, is powerful rhetoric, ridiculing Hollywood's nonsense notion of "family."

[*7] https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/07/racism-concept-change/594526/

Comments

Post a Comment